“People will do anything, no matter how absurd, in order to avoid facing their own souls. One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light, but by making the darkness conscious.” C.G.Jung

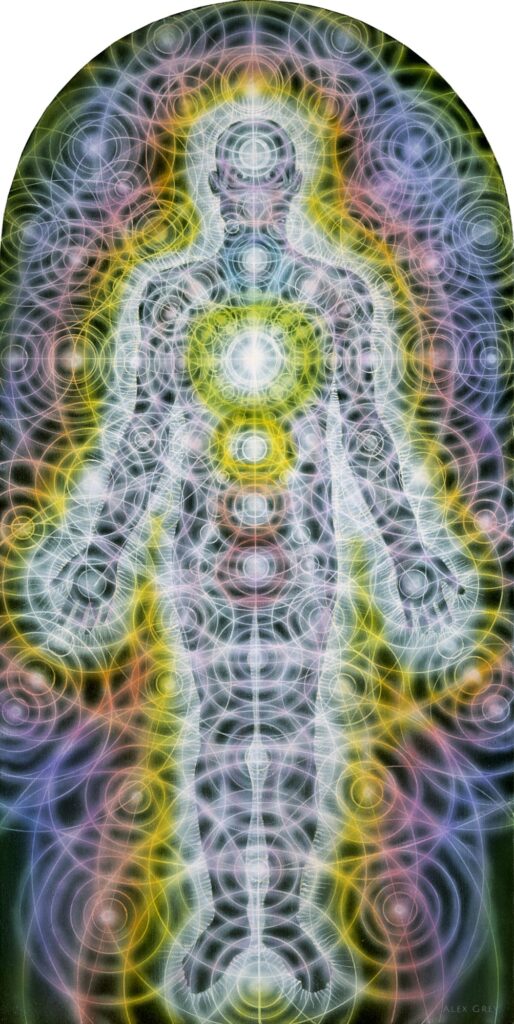

Life isn’t a straight line from alpha to omega. It’s a cycle. Going into the second half of life? It’s a u-bend. Big time. It’s a qualitatively different journey than the one you’ve been living so far. Hence the mid-life crisis. Lots of deep changes in the psyche are gradual. Take ovulation, it’s a painful anguish of not being able to expand any more into the world (if so we would crash and burn-out from being a consistent super hero mother Teresa) but instead we find ourselves on a gradual inevitable return to within, to a less expansive state, heading back towards the dark cave of the menses where the rest of the world is olympically forgotten, as we deepen within ourselves. Mid-life is no different: it is a slow gradual turning point. It’s not snap, it’s as noticeable as the sun on the day of the solstice from the preceding or following days. It’s not a snap change, nor is it the childhood game of snap: the second half isn’t the same as the first half, it has different characteristics, different depths, different colours, different energy. The second half of life, instead of constructing on the outside, is a deconstruction on the inside. Shadow work. Can I face the less than sparkling aspects of my ‘I’? Yes, that part of me that I don’t just want you to see: I don’t want see myself. Mirror, mirror on the wall.

I’m in my sixth month without menses. You might say, “Too much information”, but I can’t help but express how all absorbing it is, the sweaty sleepless nights are thankfully over along with the resultant warped mirror of the days, but even still 7 years later the body is still changing—bones, muscles, aching joints, blurry eyes, thinning hair, allergies, sagging skin, exhaustion—but more than anything is a sense of not knowing who I am, at times all encompassing, at other times a vague sensation of becoming someone/thing older/other.

The changes in my life are not so easy to accept. Who am I becoming? Part of me has died. I grieve her. I’m becoming old and I never honestly thought it would happen to me. I saw it in others. But me? The Peter Pan (or maybe Patricia Pan?) flying around the world, living it large. Yet, last week I thoroughly enjoyed myself hosting a tea party. I used all my dainty little plates. I made biscuits. The memory of my inner twenty-something-year old scoffs – she wants adventure. But I’m not adventurous any more. I’m not a backpacker but a home owner. I don’t reduce everything I have to fit onto my back, marvelling in the exhilaration of freedom as I laugh with eagerness of what might be at the other end of a long, open, dusty road. Instead now, I want my kettle and toaster to match (they are both a satisfying red).

The changes themselves are not so such big a deal. I like having my own bed. I like having a stable income. I like finding a stable ground that doesn’t move all of the time. I like having the time to become more grounded with people, to watch the seasons, to be calm. I really, really like not being in airports. In fact I like my life a lot. What’s scary is the idea of death, of my parents, my friends (many are older and not physically well) and of course, my own.

Yet, the majority of case reports of people who have had NDEs (Near Death Experiences) come back changed, they no longer fear death, as a result they are able to love more, and therefore live more. One of the tenets in the book ‘The Denial of Death’ by Ernest Becker is that the basis of all anxiety is the fear of death and that most human action is taken in order to ignore or avoid the inevitability of death. Wars, anger, strife and all the great human tensions are so often fuelled by the fear of death and avoidance of all things that put the physical body at threat. But, surely, we are not just a human body? And surely there is a way to live with less fear of what if and more love of what is?

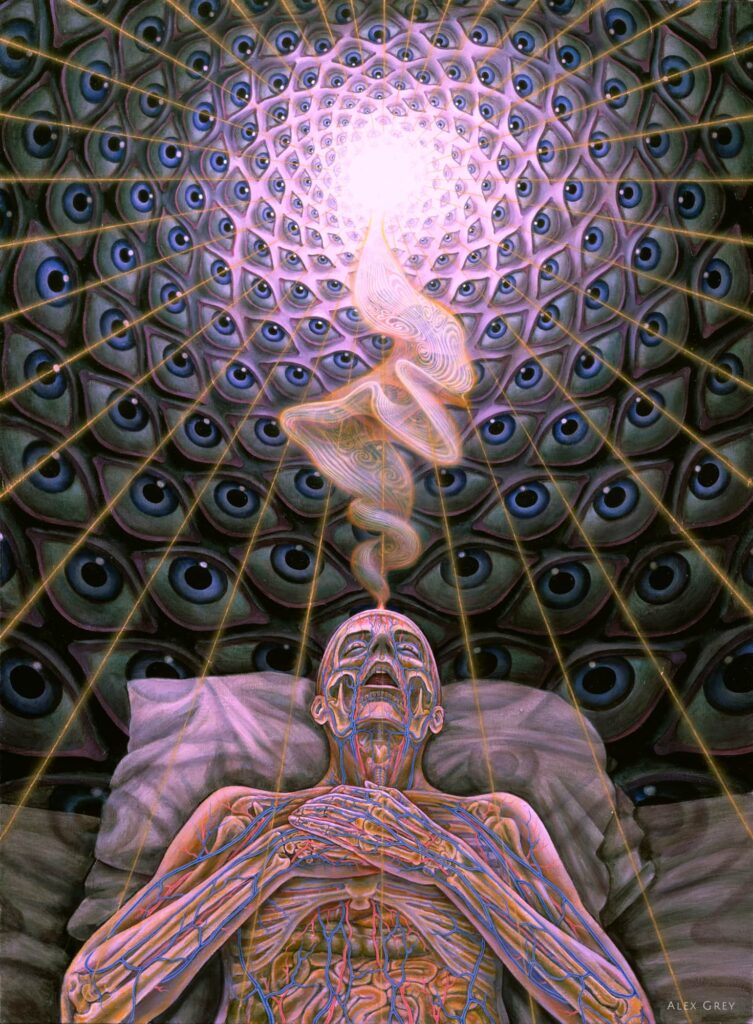

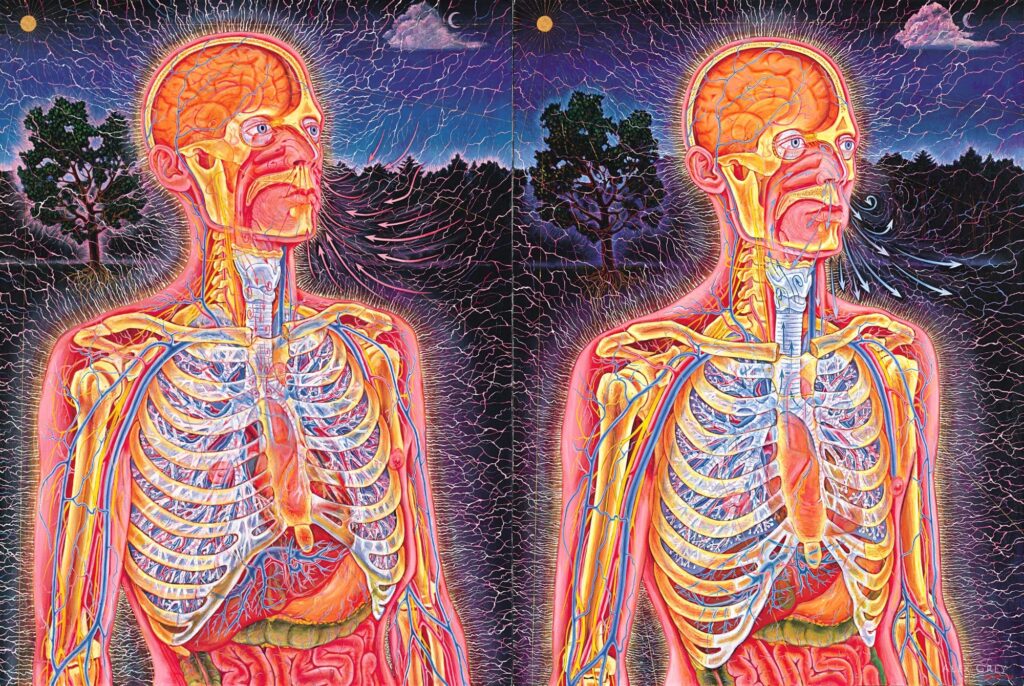

If we live in this now, this here, we find that we are breathing. Breath is life. Pranayama is a technique to investigate focusing on the power of breath for ourselves. An example of an exercise is: breathe in for four, hold for four, breathe out for four, hold for four, etc. Monks practise it for years and years, sat in peace and serenity, ever more increasing the length of the breath. In some of my sessions we practise to the count of four whereas long term practitioners may be breathing out for a minute or more. Experiencing the deprivation of oxygen held in calm acceptance, in balance and peace, causes the brain to physically change. This apparently is also true of NDEs, psychedelic journeys and intense (including abusive) life situations that have been navigated consciously. This familiarity with the mind under pressure coupled with the experience of coming out the other end, deeply aids us in the passage through death. With a practised ability to stay calm and loving in the face of death—instead of freaking out—the psyche is able to stay conscious to peacefully connect and hold Love rather than fear.

And really, what are we living well for, but to practise dying well? To me this IS the supreme goal. Yet to get there we must ‘leave behind everything, even our name, like a child leaves behind a broken toy’ (Rainer Maria Rilke). We must be able to calmly let go of our shadow, our form, our shape, our separateness and with graceful Peace immerse ourselves in the confidence of Love.

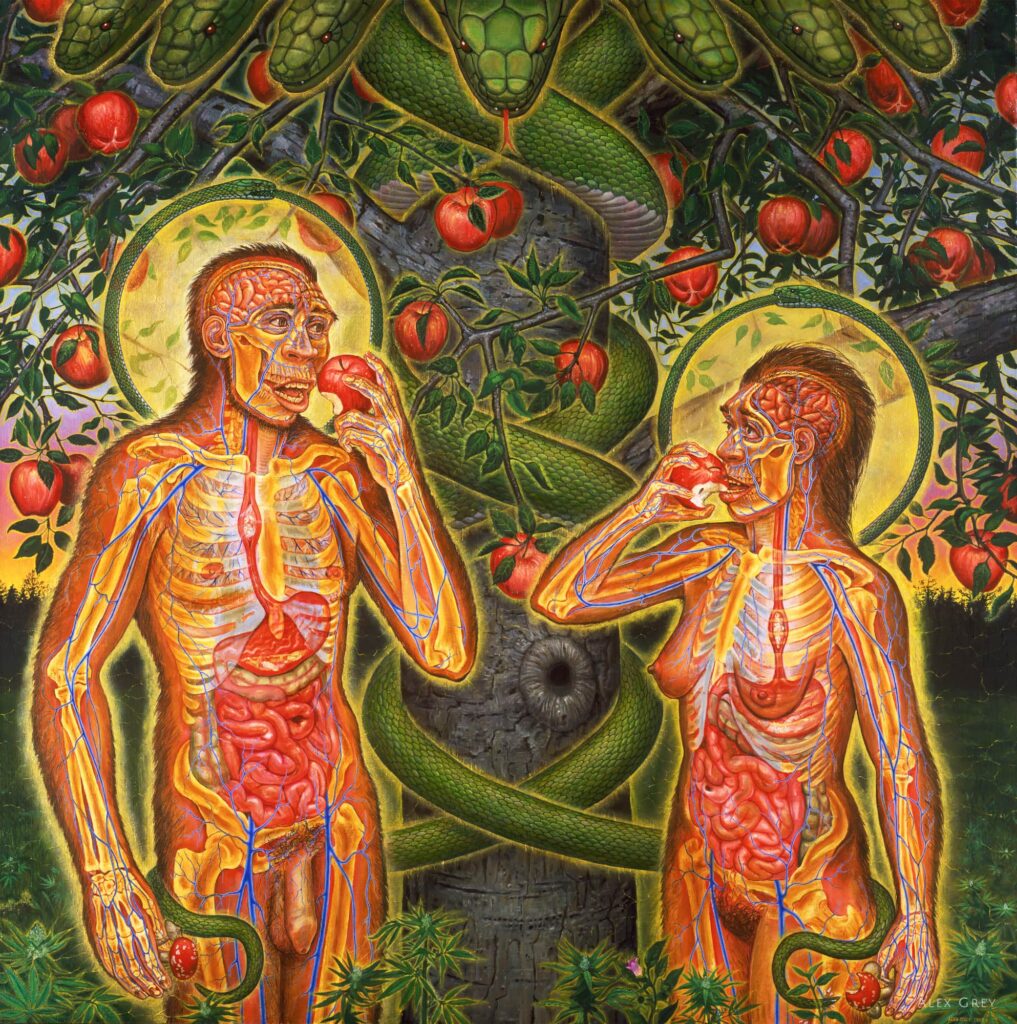

And so the second half of life is a time to deconstruct ourselves. Jung says in his alchemical texts that life is about dissolving and reforming (solutio et coagulatio). Like lungs, breathing out, breathing in. Yet, as humans we tend to have such a strained relationship with dissolution. When we resist the dissolving process we become stiff. It’s not easy to dissolve fixed attitudes, positions, ‘I’m too old to try that, or let go of that, or resolve this conflict within me’. But resisting the process of softening and hardening up again into a different shape is, deep down, a refusal to die (the great dissolution). And the refusal to die, is indeed the refusal to live, for life requires a constant rebirth of attitude. Life requires growth. Without some death, such as ego death, we cannot renew into greater softness and wiser reengagement.

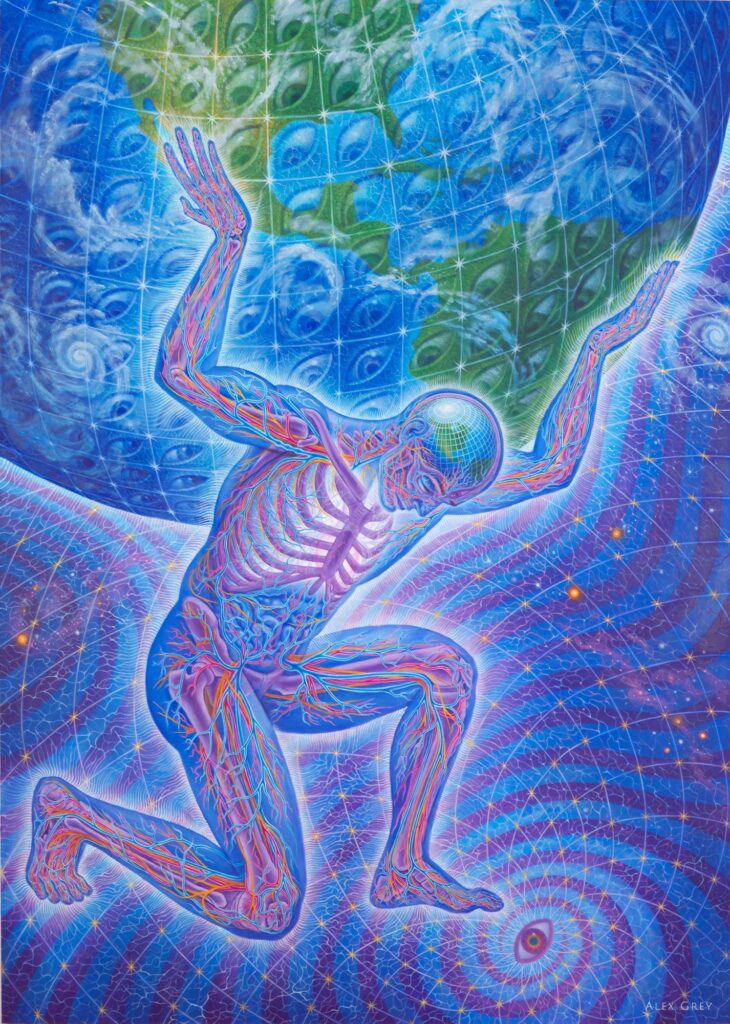

And yet, we are constantly faced with the process of dissolving and reforming throughout our lives. We are born and then have to separate from our mothers, we fall in love and then have to separate out from that unbounded oneness in order to continue living, we construct our egos and our power in the world and in midlife deconstruct in order to have a greater relationship with our essence. Finally at the end of life, death invites the dissolution of the body so to enter into the Great Solution where the spirit escapes to expand infinitely outward into the merging of all things – the fullest dissolution. If we refuse to dissolve, we stiffen. The refusal of death is the refusal to grow, and the refusal therefore to live fully.

Shamans can be considered people who have had the ultimate solutio experience: they have a death experience and are able to come back and share that light—to share with us aspects of the divine. We can see it also as being brought out from the death of ignorance into liberation. These experiences when we allow them, lead to some sense of understanding around living the life we have lived in such a way that we can integrate what is best and come to a moral and ethical sense of what we wish we could have done better, and might do better in the future. The process of dying, of letting go of our fixed images, becomes a gateway to be more in the present, to live in a better way.

And so in examining our inner world and resolving our suffering we attain a greater freedom within us. Yet what is freedom? Joseph R. Lee on ‘This Jungian Life’ says, ‘Freedom is the ability to fully express the deepest part of who we are, the divine blueprint that has been apportioned uniquely to us.’ There is a unique part of ourselves which is obstructed and if we can unobstruct the spark within us, it IS the path. According to Mystery Traditions, The Purushas (Vedic tradition), The Egyptian Book of the Dead, the Tibetan Book of the Dead and many ancient traditions the ways in which we fail to unobstruct this divine spark is something that we will have to confront after death, so why not do it now?

If we truly live through all of stages of growth and our innate potential, if we really live into ourselves, into our potential, trying to be self-aware and reflect, then when it is time to die we will have lived all of those experiences, and they will help us be less afraid because we’ve gone through the losses of various life stages and have experienced become bigger.

The message—no matter who or what we are, or where we come from— is ‘Live!’

But do it NOW! Life is now. And what gives me more confidence to live more, as I forget to play a sharp in brass band, or as I throw my racquet into the net at tennis, or swim much less than I thought I had, or start to rely on my battery rather than my bike legs, or practise psychotherapy, or cook for friends (so far no major disasters), or make love, or find myself once again single, or write a poem, or write books that I don’t know how to sell, or watch my parents getting older, or …. is Jung’s quote: “Wholeness is the goal, not perfection.”

“From the middle of life onwards, only he remains vitally alive who is ready to die with life, for in the secret hour of life’s midday the parabola is reversed, death is born. The second half of life does not signify a scent unfolding of increased exuberance, but death since the end is its goal. The negation of life’s fulfilment is synonymous with the refusal to accept its ending. Both mean not wanting to live. And not wanting to live is identical with not wanting to die.” C.G. Jung